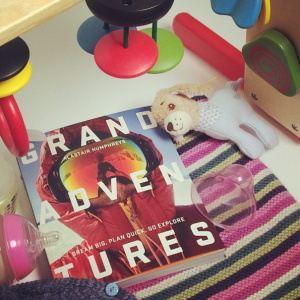

Last year I was interviewed by the extremely busy adventurer Alastair Humphreys for his website and a book on grand adventures, called Grand Adventures.

It’s out this week – I just got my copy in the post, which made a nice change from the rest of this week’s parcels (nipple pads, a breast pump and a pair of leakproof baby swimming pants!) and Monsieur Humphreys is enthusiastic that I should mention it to my own dear web following.

It’s out this week – I just got my copy in the post, which made a nice change from the rest of this week’s parcels (nipple pads, a breast pump and a pair of leakproof baby swimming pants!) and Monsieur Humphreys is enthusiastic that I should mention it to my own dear web following.

In the book he has split all of the interviews into themes, interspersed with lots of high contrast full-bleed photos, and the result is a nicely made tome for people who have smallish coffee tables or relatives who need a bit of encouragement to quit their jobs and go adventuring. Here is the original interview, as it is on http://www.alastairhumphreys.com/seaside-donkey/

A walk with a Seaside Donkey

An interview with Hannah Engelkamp #Adventure1000

A quirky, eccentric British Adventure. An impressive 1000-mile trek around the perimeter of Wales. A girl and a donkey. A £35,000 Kickstarter success backed by 829 supporters. There are a lot of fascinating aspects to Hannah Engelkamp’s Seaside Donkey journey…

Alastair: Your idea grew from watching a film about a man with a horse crossing the Sahara. Is that true?

Hannah: I had already had the idea of walking around Wales because the [new official] footpath had only been open for a couple of months, and I was just a little ripe for adventure. I thought that I would do the thousand mile walk and it would take three months or something and it’d just be a nice thing to do. And then I saw this film with a caravan of nomads heading out into the Sahara with horses and camels, and it was just that one moment, that one sort of romantic view, that vision and I thought, “Of course, I’ll be taking a donkey with me around Wales. That’s perfectly obvious.”

Alastair: Haha! Why would you take a donkey rather than just walk on your own?

Hannah: Well, I’d never actually walked very far carrying all my stuff, so I was a little bit daunted about that. I figured taking a donkey would sort that one out, and I’d be able to take luxury items like my ukulele.

Alastair: Did you take your ukulele?

Hannah: I didn’t take my ukulele, there was absolutely no time for it. It didn’t work out anything like the romantic vision I had from the beginning.

Alastair: We were supposed to take a mandolin on my desert walk but that got axed as well, for weight reasons.

Hannah: Yeah, I never really trusted the donkey not to roll on the ukulele. But also in those early days when I was dreaming about it, I thought it’d be a calm Zen-like walking meditation and that I’d take watercolours and books and a ukulele, you know, all these things that I thought I would do and learn. And it actually ended up being mostly about scooping up poo and setting up the donkeys corral and checking his hooves. It didn’t give me the kind of time and space that I was expecting.

“One of the appeals of going on a big journey is to leave behind the busyness of real life, but you’re actually phenomenally busy out on a journey.”

Alastair: It’s interesting, isn’t it, how one of the appeals of going on a big journey is to leave behind the busyness of real life, but you’re actually phenomenally busy out on a journey as well?

Hannah: Really busy, but it’s such a completely different sort of busyness, isn’t it? It’s a matter of dealing with the task at hand, the next thing to be done, and actually there is a sort of calming aspect about that, I guess. You don’t think very much about yesterday or tomorrow, it’s really just what needs to be done today in order to get myself a little further down the road and then, at the end of that to get fed and warm and dry, and also the same for the donkey.

Alastair: In the real world I hate routine, and I hate having stuff to do, but in the “real world” it’s all stuff that I “should” do, not that I “need” to do. Whereas, if you’re out on a big journey, if you just decide you can’t be bothered to walk or put up the tent or anything like that, then no one else is going to do it for you, and you’re going to suffer greatly, so the fact that you need to do it really makes you just get on with stuff.

Hannah: Absolutely. And what finer liberation as well than being able to put a message on your email saying, “I’m walking with a donkey. If you can get hold of me that’s fine. Probably texting would be better. I might not get back to you for a while.”

Alastair: Yes, I love that.

“What finer liberation as well than being able to put a message on your email saying, “I’m walking with a donkey. If you can get hold of me that’s fine. Probably texting would be better. I might not get back to you for a while.”

Hannah: There’s a real selfishness that expeditions grant, isn’t there?

Alastair: Yes, it’s very nice. I had an out of office recently from a guy saying, “Sorry, I’ve gone to live with a Buddhist monk in the Himalayas for six months. If your email is urgent please send it again in six months’ time.”

Hannah: Superb. Urgency takes on a different meaning, doesn’t it? Everything has a slightly different scale.

Alastair: Yeah, have you read Ffyona Campbell’s books?

Hannah: I read them when I was very young. I must have been in my early teens. I consider myself to be extremely different. I am not hardcore but also I don’t really want to be. But, still, I think that she probably had quite an influence on me.

Alastair: She changed her answer machine message on the day she set off to walk round the world to, “I’ve gone for a walk.” I always remember that. That’s brilliant.

Hannah: Yeah, gorgeous.

Alastair: Anyway… on the one hand then you say the donkey was a necessary thing in terms of carrying your stuff, but you could’ve done that with, perhaps, a baby stroller like Jamie McDonald who ran across Canada. So there must have been more to the donkey than just sheer sensitive pragmatism?

Hannah: Yes, yes. I’m not terribly good at solitude, but I felt like I needed to do it not with another human being. So the donkey would provide companionship, but also, of course, most of all. I’m just a showoff and I knew that people would look at me if I had a donkey with me.

Alastair: That’s very honest of you to say that, because there is quite a lot of people’s adventures that is motivated by showing off, isn’t there?

Hannah: Of course. Maybe I started out feeling a little bit sheepish that there’s something to be ashamed of in being a showoff. But actually what very quickly became apparent was that I was bringing something of interest into people’s lives. Sometimes that was really quite meaningful to people as well. So it did actually end up being something that had its own value. For example, there were a few cases where people would wheel out their sick and elderly relatives to come and stroke the donkey, and that really meant something to them if they’d been very bored and nothing much had happened for a long time.

Alastair: That’s lovely. Do you consider yourself an introvert or an extrovert?

Hannah: Extrovert, I’m sure.

Alastair: The reason I ask is that a friend of mine, he’s about to set off to cycle around the world, but dressed as a superhero. I can’t think of much I’d like to do less in life! But I cycled with him at the Tour de France up in Yorkshire, and it was amazing to see how people responded to him and his silly costume. Everyone chatting away, (although I hate people talking to me), but he absolutely loved it and he got so much more out of the experience. So I can certainly imagine how people responded to you and your donkey.

Hannah: I’ve got less interest [than you] in the idea of being in exile and complete solitude all the way. You gravitate towards deserts. Whereas I’m much more interested in people’s stories. The donkey was the way to get very quickly into people’s stories. We’d quickly dispense with what I was up to and then I would get the opportunity to ask them about themselves. Maybe they would’ve been more cagey if it had just been a journalist walking up, but because I had something to swap, it was a very quick way to get the inside track on people and places.

Alastair: The reason I initially asked you why you took the donkey was because I was comparing it in my head to when I cycled around the world. A bicycle was a wonderful way of opening doors, literally and metaphorically, but I’m sure that the donkey was an even greater version of that. Did you end up receiving lots of hospitality and random acts of kindness from strangers?

Hannah: Absolutely, people were very, very excited to have a donkey stay! And then, of course, the poor donkey just got to stand in a field and I was the one who got all the baths, and duvets, and hot meals.

Alastair: Well, at least, the donkey might win an award for being outstanding in his field…

I liked your observation of how simple a donkey’s needs are compared to a humans. Presumably you were at times feeling quite chuffed living this simplistic, minimalist life, and then you have a donkey who only needs some grass…

Hannah: Can you imagine any human coming with somebody on a five and a half month journey without, every day, having any idea of where they were being expected to go, and how far they were going to walk, what they were carrying and when they were going to stop, what was going to be for lunch? It’s astonishing to me really that he came with me at all.

And he had a moment by moment appreciation of the world. Even as I was trying to do that – not thinking about yesterday or tomorrow – in actual fact I was constantly giving myself little promises of something nice to eat if I get to the next hill, wondering what am I going to have for supper, or looking forward to setting up the tent. Everything was about marking my progress even as I thought I was living in the moment. But for him it was just about, you know, feeling like having a roll, “I’m having a roll,” or feeling like having a bit of this plant and having a bit of that plant.

Alastair: On my trips I’ve often tried to emulate being a dog to just try to be happy with whatever is around the next corner, trotting on to the end of the day and then I’ll eat and not worry about anything in-between. It’s a good thing to aspire to.

Hannah: It is and yet it’s almost impossible, isn’t it?

Alastair: I’m so bad at it. I’m forever wishing my trips away, wishing my life away. One of the nicest things I read on your website was the notion that it would be entirely possible to just stop work one Friday, pack at the weekend and head off on a trip on Monday morning.

I’m so glad to hear that, because the initial premise of these interviews was to show people how to overcome the obstacles that stop them having the adventures that they enjoy reading about, but might not actually get around to doing themselves because they think they don’t have the time or the money.

Did people often talk to you in that sort of way? Did they say, “Oh, I wish I could do what you were doing,” that sort of thing?

Hannah: Yeah, and I found it very sad a lot of the time. Often I’d get people saying, “Oh, well, I’m glad you’re doing it now while you’re young, while you can,” and they’d be people in their fifties. Sometimes I’d just think, “Oh, for heaven’s sakes, you’re just giving yourself an easy excuse.” But then, of course, you never know what other people are dealing with.

I also met a young boy who said, “Oh, I’d never be able to do this,” he can’t have been more than eight or something. He said, “I’ll never be able to do this because I’ve got asthma, isn’t that right, mum? I wouldn’t be able to do this would I because I’ve got asthma?”

And the mum said, “No, no, you wouldn’t, darling.” And I thought, “For crying out loud, don’t write yourself off yet.”

Alastair: That’s such an annoying mother. I find when I do talks at schools, when you say to young kids, “Who wants to do an adventure?” They all put their hands up. But as your audience gets older and older there’s fewer people who believe that they could actually do it.

Hannah: It’s funny though because I often found myself saying, “Oh, it’s easy, you can do something like this.” But, actually, it is quite hard. It’s not something that I’d want to complain about because it was the most fantastic six months of my life. But it wasn’t a breeze. Maybe it comes down to the fact that something can be simple without necessarily being easy.

Alastair: I like that. But just because a trip is really difficult shouldn’t be a reason to stop people beginning After all, if you began your trip and after two months you hated it, you could just quit. And at least you would know you didn’t like it and you could get on with whatever comes next in life.

Hannah: Also I think there’s a lot of emphasis put on the success. I read your interview with Ed Stafford, and there’s a real combat that, isn’t there? I know he’s an ex-army guy so maybe that’s the kind of background he has, but the whole adventure world is just infused through with this feel of trying to conquer and prove something, and I think that’s an easy trap to fall into, partly because it’s kind of necessary. If you’re doing something that feels quite difficult every day, then you do need to have some sense of the overall purpose. But I really, really don’t want that to be the way that I go out into the world, “I’m going to go out and I’m going to prove something to myself.” For me it’s much more about being a wandering minstrel, I hope. Or, at least, that’s what I’d like it to be about.

I’m not sure that was the case because I did find myself being a bit more driven by the thousand miley-ness of my adventure. One of the most arresting moments of the whole walk for me was when I met a new age traveler who was a cartwheel maker, and he said, “Oh, are you just walking around a bit with this donkey then for the summer or for a while?” And it was just astonishing to me this thought that maybe, that all this difficulty of walking around, and camping every night, and getting this donkey from one place to another that maybe I just would’ve chosen to do it as a kind of like a lifestyle choice for a while, or just a way of wandering around the place. Whereas, for me I was entirely driven by how many miles I was going to… you know, well, not necessarily. I wasn’t thinking in miles but chipping away at the total and succeeding in this challenge I’d set myself.

Alastair: That’s very interesting because that answers what I was going to ask you in comparison to Ed Stafford, because I think Ed and I are driven in quite similar ways of this need to prove stuff to yourself and to other people, and I thought that maybe women were more sensible and didn’t have that drive, and you could just enjoy the experience of going for walk with a donkey.

Hannah: I guess I don’t know. I mean, it’s difficult, isn’t it, because I’ve just proven myself to be entirely driven in that respect. I’m very aware that I’m very lucky to have done this lovely walk and it was wonderful, and I don’t want to ever look like I’m hamming it up to be something that’s tougher or more than just a person having a nice time.

The world is full of hardship for a lot of people, so to go out there deliberately to kind of add to the sum of hardship by following some rules that are essentially something that I set myself, maybe just seems a little bit contrived.

Alastair: The vast majority of adventures are very contrived: you set some sort of constraints on some sort of activity and then through the constraints comes the fun and the challenge and the rewards and stuff…

Hannah: Absolutely, and I’ve met quite a few people doing various adventures since I finished. If they’re having a really horrible time, it’s very tempting to say, “You do realise that you’re the only person who cares about this, that nobody else really even knows where you’re going?”

Alastair: Yes, yes, exactly!

Hannah: So you’re only beholden to yourself, and that’s probably worth remembering.

Alastair: Before you began, how did you overcome the very sensible concerns of jacking in your job for six months, not earning any money for six months, those sort of sensible things?

Hannah: Money was a bit of a worry but I’ve lived so frugally in the past that I knew that that could be done again, so I rented out the boat [I live on] and I’m a freelance writer so wrapping up work wasn’t too difficult.

Alastair: What advice would you have for someone then who is daunted about dropping out of work and money and the career ladder for six months?

Hannah: I’ve never really believed in that idea that you need to explain away a gap in your CV. I think if you’re a person who’s interested in the world, that ought to shine through, and having the gap in your CV which is much more interesting than another six months of progression up your particular career ladder. It all depends, of course, what area you are in, but mostly I’d have thought that doing something interesting should probably count in your favour.

Money-wise, if you do something that involves walking and camping, it’s likely to be an awful lot cheaper than ordinary life. Really it’s a matter of getting your head around stopping what you’re doing and doing something completely different.

Alastair: How did you find life on the road as a solo woman?

Hannah: Partly, I think that if you go out into the world wide eyed and enthusiastic and smiley, people respond in that way. Nothing bad happened to me but, you know, I was in Wales and there’s much scarier places that one could adventure.

Alastair: I’m not sure there’s many places scarier than Wales…

Alastair: A lot of people ask me about Kickstarter for their adventures. This is a huge topic. You had great success with it, you went significantly over your total. Why did you succeed? Was it the story, or was it the engagement with the story that you generated?

Hannah: Well, it seems to be quite widely known that you can’t get very much through Kickstarter itself. Kickstarter is only a vehicle and your pledges are mostly going to come from people that you find in other ways, so it was very useful for me to be running this after having had six months walking round the country, looking unusual. I think I had something like two and a half thousand people on Facebook, so that helped enormously because it meant that I already had people to talk to when I set up the Kickstarter. And then I set it up for 50 days, which is more than I had been advised because it is a long time to keep the momentum going. But what I discovered was that I was looking for so much cash that it was more than I could get from my existing followers. I actually needed to tell more people about it. So then I did need that extra time.

Alastair: That’s the key of Kickstarter, isn’t it? How did you get beyond your friends and family?

Hannah: It was very soon after I’d finished the walk, so the story was fresh, and I had lots of photos that I’d taken so I could make a marketing package for people that was easy to understand, and easy for them to use. I’ve been a magazine editor and a web editor in the past, so I had a good idea about how to catch people’s imagination, how to make things as easy for them as quickly as possible. Make it so that they wouldn’t need to come back to me for high-res photos or whatever it was, everything was done easily for them.

But on the whole it was down to the fact that a donkey walking around Wales did interest people. So I was very lucky. And also the real last push came through Upworthy. I researched them and made a video specially that I thought would catch their eye. I sent an email to each one of their staff saying, “Look at my video.”

I started out thinking that I need to get into the broadsheets, and that was useful, of course. But actually it’s much more vital to get your story in front of people who are sitting in front of their computers and can click through right now. It’s all about making things easy for people.

I went on the radio four or five times and I don’t think that that yielded a thing. It was very good fun to do, and there’s been a lot of people I’ve met since who have said, “Yeah, I’ve heard about you and your donkey,” and they couldn’t quite put their finger on how they had heard, so that is also somehow useful.

Alastair: That’s all great advice. I think a lot of people see Kickstarter as a way to get people to pay for their adventure upfront, but what you’ve mentioned firstly is the need for a brilliant story (the donkey). Secondly, you’d already done your trip, so people knew about you, you had already achieved it. And then, thirdly, you met the challenge of reaching an audience beyond your friends. I think they’re good cautionary tales for anyone who thinks Kickstarter is just free money.

Hannah: I’m not at all sure that I would do it again. For anyone who did want to do it, I would say that it’s worth taking into consideration that you’re selling yourself and you’re selling your idea to people, and that is really quite hard on the soul, in a way. For 50 days, I just lived hitting “refresh” on the page to see if anybody had put some more money in. That was really uncomfortable because I’ve striven, I think, to be not that bothered about cash in my life, and suddenly I found myself just living for this little total on the screen. It was almost unbearable to have this amazing outpouring of support, backed by the money from all of these people, and yet to look at it and just be thinking, “It’s not enough, it’s not enough,” and yet it was, you know, thousands and thousands of pounds!

That was horrible. I found that really difficult. By the end I really thought, “Good God, there’s easier ways to make money for your adventure.”

Alastair: And there’s a lot of pressure on you now to deliver something that’s worth their money.

Hannah: Yeah, absolutely. I’m past my self-imposed book deadline now! So I’m just having to be very apologetic at the moment.

Alastair: My last question is if I gave you £1000 for an adventure, what would you go and do?

Hannah: That’s such a nice daydream to have. On the walk with the donkey I was so driven by it being this thousand mile journey, and yet on a day to day basis what was so delightful was heading out without a destination.

So if I had £1000 I would probably just leave the front door with my camping kit in a bag, and I’d just walk. I’d probably want to walk to the Channel, and then perhaps once I got there I might try and find a port and see if someone would give me a lift, and then just keep on walking. And I figure after a while there wouldn’t be footpaths necessarily any more, perhaps there wouldn’t be good maps, but it’d just be really interesting to walk without a destination, away from home day after day. It wouldn’t be very expensive so that £1000 might last a very long time.

Alastair: That’s a very lovely answer. Thank you.

Hi Hannah,

I’m a bit of a luddite and can’t seem to figure out where I was meant to access what I purchased. Was it meant to be emailed or was there a place to download that I missed? Apologies.

Hi Pamela,

Apologies, my fault. I’ve not yet managed to get the ebook and download out as there has been a series of technical difficulties behind the scenes with this website when I try to add the downloads to the shop. It’s getting sorted, but I keep being held up by this tyrant of a tiny baby that I have made! I’m very sorry, and it is at the absolute top of my list… I’ll be in touch very soon!

Hannah x